So there's this Roman emperor...

How I learned about the real-life Emperor Geta and why I'm about to be so annoying about Gladiator 2

Despite my deep and abiding love for all things ancient history, I have never been one of those people who thinks about the Roman Empire every single day. I find it a fascinating part of world history, as I do almost any ancient civilization, but it was never in my top three (in order: Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece, Ancient Britain). In fact, until just a few weeks ago, I really had not thought about Ancient Rome at all, except when I’d listen to my mom gush about it for hours at a time (she happens to be part of that demographic at the moment).

However, as of late I’ve had cause to ponder the Roman Empire quite a bit more often than I usually do. One particular cause, in fact. You already know what it is if you’ve clicked on this article, so I’ll quit it with the preambles.

Part I: In which I acknowledge that, yes, it’s just a film…

Gladiator II is the sequel to Ridley Scott’s y2k classic Gladiator, and follows a young soldier-turned-gladiator named Lucius who sets his vengeful sights on the leaders of the Roman Empire for conquering his home and causing the death of his beloved. Unless you’ve been living under a rock (or you’re not a fan of Joseph Quinn, Paul Mescal, Pedro Pascal, or anything Ridley Scott has done), you probably know about this film and its predecessor, and you don’t need me to tell you how huge it’s going to be when it comes out in two days.

Full disclosure…I’ve actually never seen the first Gladiator.

Do I fully intend to watch it at some point in the near future? Yeah, probably.

Do I also intend to watch Gladiator II at some point in the near future? I don’t know. Maybe.1 When it comes out on DVD. (Leave me alone.)

The only thing—and I do mean the only thing—that would stop me from doing that is something which, I believe, no self-respecting student of film should get too up in arms about, especially when it involves people we know next to nothing about: historical inaccuracies.

Here’s where I lay out my hypocrisies when it comes to historical accuracy in film and TV, using Bridgerton as an example: I could not care less about all of the anachronisms and inaccuracies in that show, from the fashion to the cast of multiracial characters, to the music. I know that those kinds of things mean a lot to some people, but for me it just gets in the way of my enjoyment of the steamy, compelling romance plots. I visit the world of Bridgerton for an escape from modern, colorless (romance-less) life, and that’s all it ever needs to be, in my opinion.

The same, you would think, ought to be said about the Gladiator movies. And I will be the first to concede that getting in a tizzy about the portrayal of an Ancient Roman emperor who probably didn’t contribute much of value to his community and died long before he could have done anything of note, is not a wise use of one’s time. In many ways, these characters are blank slates since they all lived so long ago and there are so many different interpretations of historical records anyway. For all we know, Nero may not have been as bad of a guy as the annals report.

And yet…

Part II: In which I ignore all that and proceed to point out every single way Ridley Scott gets the Severus Bros WRONG

Them’s fightin’ words, Mr. Scott! Completely unbeknownst to him, of course, I have no life, so it looks like he’s just gonna have to deal with me and my ilk for the foreseeable future.

So let’s begin with the stupidly obvious, shall we?

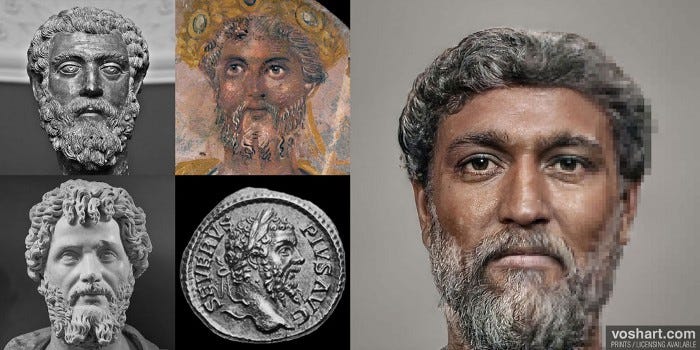

1. Why are they so pale?

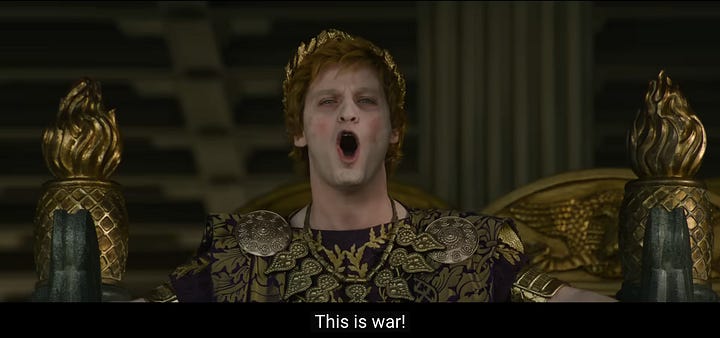

Perhaps the most immediately striking feature of our cinematic Severus Bros is how gaunt and deeply underslept they both look. Apparently anemia is one of the symptoms of moral depravity. Certainly plenty of big screen villains have sported the sun-deprived pallor to visually communicate that something is seriously wrong with these individuals (and not just medically). However, I appreciate the use of this tried-and-true tactic because, yeah, they look scary as hell!

Practically vampiric.

The reason I bring it up here, though, is because…they really shouldn’t be.

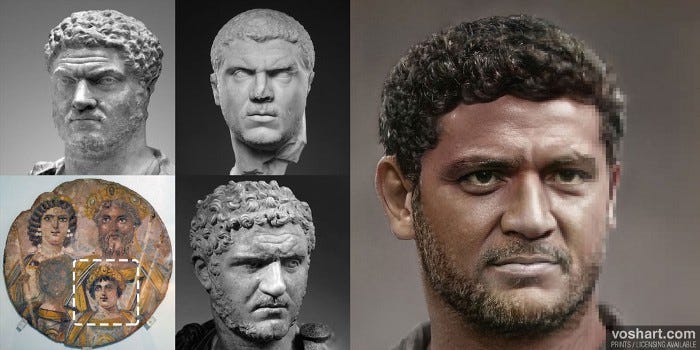

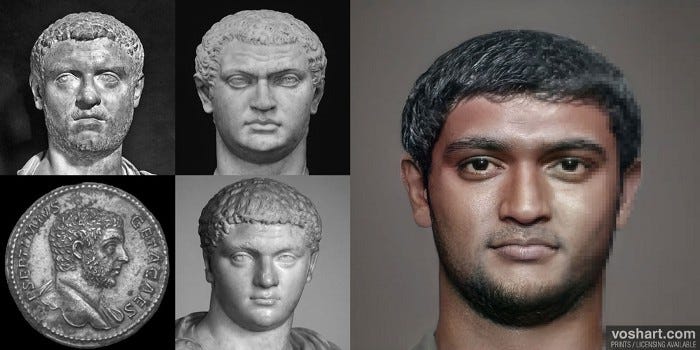

According to Wikipedia2, “A strong distinction in skin color is frequently seen in the portrayal of men and women in Ancient Rome. Since women in Ancient Rome were traditionally expected to stay inside and out of the sun, they were usually quite pale; whereas men were expected to go outside and work in the sun, so they were usually deeply tanned.” Add to that the fact that Septimius Severus was born and raised in North Africa, and most likely would have been dark-skinned—in fact, he is widely regarded by historians as “the first African emperor of Rome”—it’s not a stretch to conclude that his children would have been mixed race.

Certainly not translucent. Now there is an argument to be made that we really can’t presume to know the actual skin tone of ancient peoples, even based off of where they grew up. It’s certainly the case today that most people in North Africa tend to have lighter skin than Sub-Saharan peoples, and the Mediterranean is home to plenty of light-skinned folks. That same SlashFilms article, written by Hannah Shaw-Williams, argues that,

“While Africa and Black identity are often treated as synonymous in modern society, the ‘Africa’ of the Roman Empire was limited to a small portion of North Africa that today includes countries like Tunisia, Libya, and Algeria, and was formerly part of the Carthaginian Empire before Carthage was conquered by Rome. We can debate back and forth (and people certainly have) about how much melanin the ancient Carthaginians typically had in their skin, and how much of it would have filtered into Caracalla and Geta’s particular blend of Roman, Libyan, and Syrian genetics. But trying to transplant complex modern concepts of race onto Ancient Rome is like trying to stick a triangular block through a square hole.”

But still…I’m going to go out on a limb here and argue that the Severus Bros would have, at the very least, had a healthy bronze tint, rather than the pasty, glittering skin of a killer.

2. The strange case of the Freaky Friday-esq body swap of Caracalla and Geta

Here’s where things get a little weird. For me, at least.3

Say what you want about Scott’s portrayal of Commodus in the first Gladiator movie, but at least he was somewhat comparable to his real-life counterpart. I’m honestly not sure what he was thinking when he chose to write Caracalla and Geta like this.

For one thing, in the new Gladiator movie, Geta seems to be the elder brother, and Caracalla the younger. Even though, in real life, Geta was born one year after Caracalla, in 189 and 188 AD respectively. Some sources have said that at the start of casting, Joseph Quinn was originally meant to be Caracalla, which would make a lot more sense for their apparent characterizations. Aside from Fred Hechinger’s portrayal of the younger brother as flamboyant and shallow4, Caracalla was, by all accounts, every inch the military ruler, and had an exceptionally fragile temper. If he had remained as Caracalla, that would’ve been a major point in the movie’s favor, historical accuracy-wise. But Quinn is instead playing Geta, which brings me to the thing that irks me the most about his characterization in this film. Emperor Publius Septimius Geta was, according to every source I could find, the vastly more sensitive, learned, and administrative of the two brothers.

Despite the haunting lack of information about him—for reasons I’ll get into in the next part—there seems to be just enough evidence to suggest that Geta was far from the crazed ginger demon we’ve seen thus far. “In his time” writes historian Franco Cavazzi, “[Geta] became quite literate, surrounding himself with intellectuals and writers. He showed his father much more respect than Caracalla and also was a far more loving child to his mother.” Cavazzi also says that Geta “suffered from a slight stammer,” but I haven’t been able to confirm whether this is true from any other sources, so take it with a big grain of salt.

Historians are pretty universally in agreement about how different from each other the two brothers were, further feeding the widely held perception of Caracalla as the brutish tyrant and Geta as the favored son. Much of this may be little more than speculation based on the scant clues we have about their individual personalities, but we can infer that the dichotomy between the two brothers was wide enough to create a rift in the empire itself (that could only be healed by the administrative genius of their mother, Julia Domna, but we’ll come back to her). According to YouTuber Accessible Art History,

“Even though they were only a year apart in age, the two royal brothers could not have been more different. Caracalla, the elder of the two, was known for his fierce and aggressive nature. He was ambitious, ruthless, and had a militaristic outlook. He was often eager to prove his strength and dominance. In stark contrast, Geta was more reserved, intellectual, and inclined towards the administrative side of ruling the country. Their differing personalities and approaches to leadership further fueled their animosity. They simply couldn’t see eye-to-eye on how to rule an empire.”

The more you learn about what these two emperors were like in real life, the more bizarre Ridley Scott’s decision to diverge so far from the truth (which, in this amateur historian’s humble opinion, is way more intriguing than fiction) becomes. As I’ve stated above, I understand the motivation behind making the Severus Bros more villainous in order to raise the stakes of the story and thus make the hero’s quest for vengeance that much more heroic. But the question I always come back to, then, is why would he change them so thoroughly they become essentially made-up characters with almost nothing tying them back to their historical namesakes beyond, well, their names? Geta has become the older brother who is obsessed with power and glory, meanwhile Caracalla has backslid so far in his portrayal, he’s unrecognizable from either of the real-life figures.

Joseph Quinn himself stated in an interview with EW, “Geta certainly plays the role of an older brother…Caracalla is having some cognitive erosion occurring in one of his lobes in the brain. And that is affecting his ability to be cognizant and conduct himself in a way that’s becoming as a young emperor.”

So Caracalla has a cognitive disability now. Great. I’m sure that’ll be handled with much tact and respect as we root for these two over-the-top villains to die horrible deaths. Hey, I’ll take my diversity wins where I can get them!

(Maybe that’s why he keeps saying “war” all the time…🤔)

All jokes aside, I really can’t fault Scott for that character decision. Even if we ignore the Trump-sized elephant in the room, there is a plethora of examples of corrupt rulers throughout history5 who showed clear signs of mental and emotional decline. Though whether they were the cause or the result of such corruption is never clear, and perhaps ought not to be, given how often these historical figures have been used to demonize and stigmatize the mentally ill and disabled. Perhaps Quinn’s “Geta” serves as a counterpoint, showing that a ruler can be just as wicked and morally bankrupt with all his mental faculties (seemingly) intact.

3. They hated each other, your honor.

Caracalla (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus) was made joint emperor with his father in 198 CE, at the ripe age of ten. Although Geta, eleven months younger than Caracalla, was named “caesar” (heir) in 198, he did not become joint emperor with is brother until 211, upon the death of their father. Reportedly6, Septimius Severus’s final words to his sons were: “Be good to each other, enrich the army, and damn the rest.” It has been stated, ad nauseam, just how thoroughly Septimius failed to instill the first part of this request in his sons.

Prior to his death, Septimius Severus had brought both his sons with him on a campaign to Britain, in an effort to show them the ropes of ruling an empire, and to try to get them to stop quarreling incessantly. By all accounts Geta and Caracalla thoroughly despised each other, probably from the moment they were both made heir. Septimius’s strategy, ill-advised though it turned out to be, was to bring them closer together by giving them shared responsibility of certain aspects of governance. Geta took charge of civil administration, while Caracalla went to Scotland with Septimius to continue their campaign.

It was during this protracted military roadtrip that Caracalla allegedly tried to murder his father on several occasions (according to both Dio and Herodian). Although he did not succeed, Septimius did eventually die, in modern-day York, of an unspecified illness.

Once their father had passed, Geta and Caracalla were officially declared joint emperors and promptly returned home, there to continue their never-ending mission to kill, disavow, or otherwise back-stab each other until one of them remained standing as the sole emperor. The promise of power has always had a way of corrupting the bedrock of any family fortunate enough to have it.

According to the YouTube channel Walks Inside Rome,

“Septimius Severus died in 211, leaving the rule of the Roman Empire to his two sons, Caracalla and Geta. From the beginning of their joint reign, these brothers had a very strained relationship. Their mutual mistrust meant that they always surrounded themselves with armed guards in case either brother made an attempt on the other. Caracalla, however, ultimately proved more devious.”

Ridley did get one thing right, at least. These two were, very possibly, massive pricks to one another, and, by extension, to the country they were meant to govern. Geta may have been the one to actually give a shit about other people beyond just himself, but at the end of the day, they were both spoiled princes who were given far too much power far too early in their lives. And, for better or worse, they both wanted more.

In the end, however, Caracalla was the one who triumphed. “Cassius Dio tells us that on December the 26th, 211, Caracalla asked their mother, Julia Domna, to organize a private meeting in her apartment so the two brothers could discuss a truce.” Geta arrived unaccompanied by his guards, and was swiftly and brutally attacked by one of Caracalla’s guards, who stabbed him several times in front of their horrified mother. Geta, only 22 years old, bled to death in his mother’s arms.

Remember when I mentioned the stark absence of substantive information in Geta’s case? That is as a result of the damnatio memoriae (literally “damnation of memory”) undertaken by Caracalla following his brother’s assassination. He spent a considerable amount of time and resources wiping out any traces, visual or otherwise, of his ill-fated brother: records, coins, arch friezes and even family portraits. You name it, he deleted it.

Caracalla also gave his wife, Fulvia Plautilla, the same treatment after he had her exiled and then assassinated—he wasn’t on good terms with her either—but that’s another story about another woman completely erased from Scott’s epic narrative.

Let us take a moment to talk about the stone-cold legend that was the dowager Empress Julia Domna

Ridley Scott you will forever be on my shit list for denying this incredible lady the chance to be portrayed on the big screen.

Because let me tell you, this woman was so freaking cool.

Born in Syria in 160 CE to a powerful and highly influential family7, the future empress married General Septimius Severus in 187 CE. He was a widower, and their meeting was supposedly the result of both receiving a cosmic portent of their impending marriage.

“[Septimius Severus] came to Syria on the advice of an omen, which stated that Severus would find his second wife there. He met […] Julia’s father […] who introduced him to his youngest, unmarried daughter. Julia Domna’s horoscope had predicted that she would one day wed a king: this would have proved irresistible to the prophecy-minded Severus.”

As empress, Julia Domna was an esteemed patron of the arts and personally supported, lauded, and otherwise hobnobbed with members of the empire’s learned society. Not only was she astoundingly learned herself, but sources claim that her husband, and later her sons, often consulted her in matters of governance and public relations. She was, essentially, an unelected official.

At one point during Septimius’s reign, Julia Domna was accused of adultery as a result of her struggle for influence over her husband with Plautianus, his praetorian prefect. Don’t worry, though, she totally won. That fake bitch got executed for plotting to overthrow their family.8 She traveled extensively with her husband and sons during their campaigns in the east and west. After Septimius’s death in Eboracum (modern day York), it was Julia who persuaded her sons to accept their father’s dying wish that they share power and rule as joint emperors.

From then on, she acted as the primary mediator between Geta and Caracalla and was largely responsible for holding the empire together when they tried to split it in two. They literally only felt safe in each other’s company provided their mother was there to keep some semblance of peace. This, of course, did not last.

“According to Cassius Dio, Geta died in Julia’s arms, and Julia herself was so thoroughly covered in Geta’s blood that she failed to notice that she had sustained a wound to her hand in the attack. After Geta’s death, Caracalla became the sole ruler of Rome, and he immediately instituted a damnatio memoriae against Geta […] Because of this policy, it was likely unsafe for Julia to express any sorrow over [Geta’s] death, even in private, for fear that Caracalla would also have her assassinated.”

Yet, when Caracalla became sole emperor, Julia Domna maintained her role in the politics of Rome, remaining one of the emperor’s most trusted advisors and, for lack of a better analogy, “first lady” of the empire. She kept the home fires burning—although she spent most of her time in Antioch—and in 217 CE survived her eldest son when he was assassinated by his own men in Syria. Macrinus, the man who brought about Caracalla’s death and succeeded him as emperor, was well aware of her political prowess and influence, letting her keep her place at court and all of her attendants.

After trying and failing to stage a coup to become Rome’s first sole Empress, Julia Domna was forced to leave Antioch, and, whether due to her fear of losing power and security or as a result of her late-stage breast cancer, she eventually died of starvation at the age of 57, not long after Caracalla’s death.

So widely beloved was this woman that, following her death, she was deified by many people across the empire, including her nephew (and successor to Macrinus) Elagabalus. In this author’s humble opinion, Ridley Scott missed a cinematic DIAMOND MINE in choosing to leave out such an undeniably fierce and compelling historical figure, not to mention “one of the most powerful and active empresses in Roman history,” according to Ulrich Hiesinger. As a director and a storyteller, you could hardly go wrong with a female character so badass that four different emperors deferred to her when things got messy in Rome.

One final note before I let you get on with your doubtlessly stressful work day:

Elagabalus, is that you??

I was today years old when I learned that Elagabalus (famously portrayed by Mathew Baynton in the CBBC hit series Horrible Histories) was actually their cousin, and became emperor after Caracalla kicked the bucket!

I suppose it makes sense, then, that Ridley would get a little confused trying to differentiate him from his predecessors. They were, at the end of the day, a bunch of rich little pricks who tried and failed miserably to run a government which spanned most of the western world at that time. You can hardly blame Hollywood for getting them mixed up. Besides, as a sentimental man once said, “The best way to bring folks together is to give them a real good enemy.” Can’t argue with that logic, especially when it comes to the Gladiator movies.

Anyways, if you’ve made it this far, I deeply, deeply apologize for wasting your time. I’m not even going to see this movie when it comes out (I’m going to see Wicked for crying out loud)!

Sources

https://www.slashfilm.com/1620982/gladiator-2-emperor-brothers-villains-real-history/

https://roman-empire.net/decline/geta/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geta_(emperor)

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13004/geta-facial-reconstruction/

https://www.worldhistory.org/Julia_Domna/

https://www.worldhistory.org/Caracalla/

https://www.worldhistory.org/Septimius_Severus/

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13003/caracalla-facial-reconstruction/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Publius-Septimius-Geta

https://ancientromelive.org/geta/

https://www.unrv.com/emperors/geta.php

https://www.livius.org/articles/person/geta/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_people_in_ancient_Roman_history

https://medium.com/@LesliePoku/the-african-roman-emperor-septimius-severus-cdbbe837d8b0

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julia_Domna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commodus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulvia_Plautilla

Read: If Joseph Quinn is delicious enough to entice me. Which he probably will be. So I’m screwed.

I know, I know, not the most universally accurate of sources, but just let me cook for a minute.

Let’s not forget this entire article is self-serving and adds next to nothing of value to any relevant conversation about film or history. I just like to bitch and moan.

Flamboyant though he may have been, shallow he very much was not, according to most accounts.

Looking at you, Caligula and Henry VIII.

According to the Roman historian and senator Cassius Dio (77.15.2).

Her father was a high priest and her elder sister, Julia Maesa, was grandmother to future emperor Elagabalus.

Nobody wants to say it because it’s a little cringe now, but I’m gonna say it anyway: Julia Domna was so BRAT.

Submit this review/opinion piece to the entertainment section of the hippest paper or culture website you know of, Celeste! You should do this kind of writing as a second gig--you'd start SO many conversations about film! Great read, thank you!